By Annabel Murphy

It’s early morning in May and Dutch farmer, Jos Verstraten is busy harvesting the first cut of grass on his sandy soil farm in the south east of the country, close to the German border. The harvest will be dried, compressed and stored to use as feedstock for 150 dairy cows during the winter months.

It’s been a much better start to the season with enough rainfall to keep the grass green and soil moist for the following spring harvests. This is a different story, he said, to the last “five to six years” where abnormally intense heat and dryer months made farming difficult and unpredictable.

Verstraten, who is also a board member of the Netherlands Agricultural and Horticultural Association, LTO, has been a dairy farmer for 35 years and has never before experienced climate change this way. The warming effects are felt “every day” on the farm.

“Last year we were irrigating our crops because it was already too dry in May and that was the case for the few years before that too. This year there is more rain luckily, but we as a farming community feel very uncertain – just look how dry southern Spain is so far this year,” he said.

The Dutch agricultural industry is facing enormous upheaval. The country is the world’s second largest agri-exporter and has the world’s densest population of livestock, having a significant environmental impact on biodiversity, air, water and soil quality in the surrounding environment. How to solve this complex issue is being faced head-on between governments and farmers.

Some members of the Dutch government have said the industry must halve the number of livestock to dramatically reduce ammonia levels in the atmosphere and nitrogen deposition. Consequently, farming protests and demonstrations have been ongoing in The Hague.

“We have a crisis here in the Netherlands, both the nitrogen reduction issue and a changing climate that we are not used to. Climate is a bigger threat for the long term and we’re experiencing and preparing for it nearly on a daily basis,” he said.

Last eight years have been the warmest on record globally

Verstraten’s story is just one example of the harsh reality of an already changed climate. The picture was put into stark perspective in the latest European State of the Climate (ESOTC) report, published last month by the Climate Change Service CS3, part of the European Commission’s Copernicus Programme.

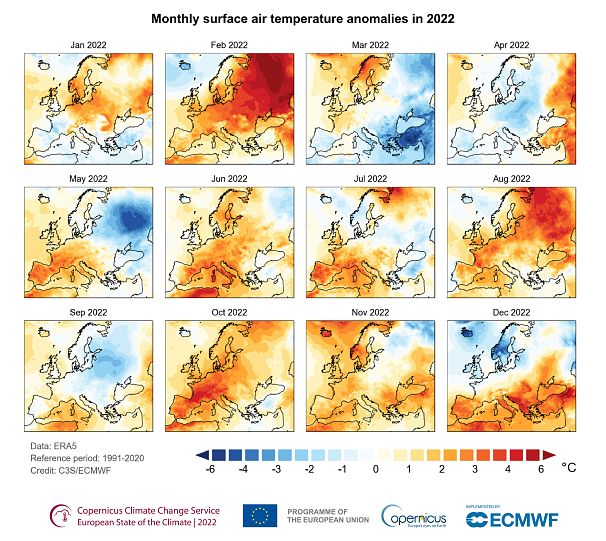

Analysing satellite and in-situ data sources on a range of climate variables such as glacier melt, surface air temperature and hydrology, scientists said this past year was the hottest on record for Europe – with an increase of 1.4 degrees Celsius above average temperatures over the 2022 summer.

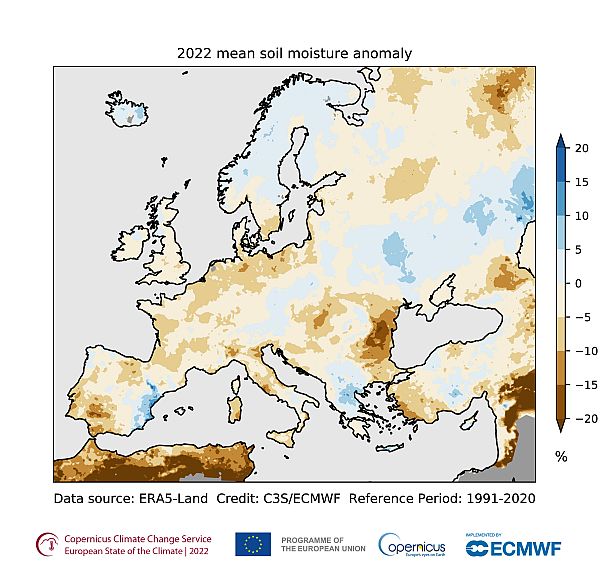

Data also showed soil moisture levels were the second lowest in 50 years over the continent. The lack of precipitation and more evaporation of surface water due to extreme heat increases the dependence on irrigation methods and energy use in industries like agriculture.

The report also went on to say that extreme weather events were likely to persist as record high emissions in the atmosphere continue to warm the climate, increasing the chance of abnormal weather conditions.

Atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) concentrations also reached their highest levels globally since monitoring began in the early 90s. Carbon dioxide has increased by 2.4 parts per million (ppm) per year since 2010 and methane increased by 1894 parts per billion (ppb) above annual average levels.

Adaption mindset for a changed climate reality

Carlo Buontempo, Director of the C3S described the findings as akin to being in “uncharted territory”.

“The report highlights alarming changes to our climate which have consequences for biodiversity, communities and whole industries across the EU. We are at a point now where we cannot stop the climate from changing and the attention must also focus on mitigation and adaptation to a new climate – we can’t go back to what it was,” he said.

Verstraten said he wasn’t surprised to learn that warmer and dryer days are on the rise across Europe and believes there is no silver-bullet solution, but Dutch farmers are working to improve climate resilience.

“I have two irrigation systems now as well as cooling fans and sprinklers in the barn for our cows. Also, growing corn as a substitute to grass for feedstock is being considered by farmers because it grows better in drier, more tropical climates,” he said.

However these alternative solutions are not necessarily sustainable either. When whole industries are relying on irrigation and pumping water from the environment to protect their farm, it impacts biodiversity in the surrounding areas, leading to more debate around fair and appropriate use of water – particularly in times of drought and extreme heat.

Also, simply replacing grass with corn fields may bring other ecological issues. Grass acts as a carbon sink, helping to strengthen biodiversity and reduce the impact of nitrogen contamination in groundwater due to its absorbing and intensive root system.

“We don’t have all the answers. We want more help in understanding how to best adapt our farm and that’s not happening fast enough. The sector is very vulnerable to climate change which also impacts energy prices, import of feed or for fertilisers,” he said.

Designing an accessible and actionable climate service

The transition to a greener, more sustainable economy, one that works in harmony with nature, will take time, innovation, information and sacrifice.

Copernicus provides climate data freely and is working to convert it into actionable insights through applications for European businesses, local governments and urban planners to support the transition to a greener society.

Their scientists have established “sectoral information systems” which provide tailored climate information, models and applications relevant for specific user groups and industry sectors, such as agriculture.

One such example is the Copernicus service for the water sector, made up of water-related datasets and interactive web applications to help water managers and related industries plan for changes in climate or seasonal forecasts, such as expected rainfall and river discharge (volume of water in rivers).

Peter Berg, Head of the Hydrology and Research Unit at Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute and lead scientist for the Copernicus water service application says it’s important to make climate information actionable and straightforward, so non-technical people can apply it.

“The water service applications show changes in many water related climate indicators, for instance seasonal forecasts about how much water there is in nearby rivers. This information helps for long and short term planning – it’s important to help the European community understand and prepare for climate change,” he said.

Understanding and prioritising between different user groups

Part of building climate resilience and adaptation strategies means understanding the broader ecosystem of water and how it is used. Having a European protocol for collaboration between all stakeholders about how to best utilise natural resources is important, particularly for rivers that flow through multiple countries.

“It’s beneficial to have a dialogue and a common protocol in place so all parties can work together to prioritise water. There are many sectors with significant needs, for example agriculture, tourism, hydropower, the cooling of nuclear power plants, as well as environmental and biodiversity flow.

“You need a common space and guidance on how to prioritise and use water. This is something we are working on in Sweden,” Berg said.

Competing priorities and values are a reality in the green transitions which is why collaboration between governments, environmentalists, universities, investors and communities is even more critical.

More formal dialogue and mediation processes that lead to viable agriculture solutions is something Verstraten says would bring more confidence to the Dutch farming community who are worried about their livelihood.

As we end our interview, Verstraten contemplates the enormous challenges for over 14,000 Dutch dairy farmers he represents as board member of the LTO industry body, but also worries about the situation closer to home.

“If it was just me, I would be fine to leave the industry and retire in a few years. Let others figure out how people get their food amid all of these issues but my 28-year old son, Lucas wants to stay in farming and continue the tradition, so I fight on.

“I worry about the next generation,” he concluded.